I said in a previous post about Digital planning that the Spatial planning must be the revised result of the transactions which are carried out there by the digital plans approved. This transformation of the plans into transactions is called Systematization (we will talk much more about systematization). Well, both digital plans and the revised spatial planning must be recorded in a data base that we denominate Digital Recording of Planning.

It will be a recording regulated by the body responsible for urban planning. This recording acquires a particular character because its content has legislative status. That is why we say that it cannot only be an administrative recording like the ones that serve to improve the organization of public management. It must be a legal recording because its content affects the capacity of citizens and landowners to act.

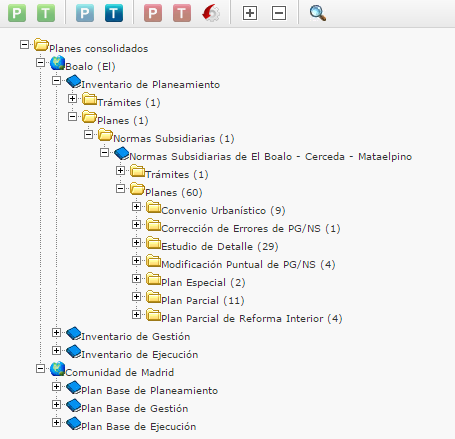

In Spain, there are three levels with urban planning competency to formulate spatial planning instruments: the national level, the regional level and the local one. The lower the geographic area studied, the greater the level of detail of its plans. This determines the first problem: How many recordings are needed?

Suppose that each level has its own characteristic recordings. There will be a national recording, seventeen regional recordings and approximately eight thousand local recordings. If all of them published their information by means of standard web services, we would be able to obtain through the Internet the three current spatial plans for every part of the territory and a complete, continuous and updated map of the current spatial planning (Development plan).

In this scenario, it makes sense that the municipalities group together in order to obtain scale economies when establishing the recordings. No matter if they do it as county council municipalities, as districts or as provincial councils. This grouping process is necessary and unstoppable, not only for the planning but for nearly every process of local management. Especially, in small and medium-sized municipalities.

The second question is: What instruments must contain each recording? The recording must contain the instruments the level is going to use. The Local General Plans are a clear case. In fact, the competence to approve them tends to be shared by the local level and the regional level. However, it is the local level the one in charge of their implementation. Therefore, the local recording will be in charge of their management.

The third question is: Is there any type of integration or communication among the recordings? The distribution of urban planning competence among these three levels determines the existence of two simultaneous flows of information:

- A downward flow of “change orders”. It takes place when a superior level needs to alter the current spatial planning of an inferior level.

Due to the incredible change resistance of the spatial planning, the “orders” can take many years since they are issued until they are executed. This period of transience tends to cause many problems because the inferior level’s current spatial planning remains completely or partially suspended during that period. We are going to call this flow: Adaptation. In the European Union, the transposition of directives to national legislations operates similarly.

- An upward flow of information. It takes place when superior levels require data of the inferior levels about the state of its spatial planning or its development. It is useful in order to propose and establish improvement strategies or land use policies more suitable for the needs. We are going to call this flow: Feedback.

In the present situation, with planning on paper, both flows are very complicated, slow and can even be functionally and economically non-viable. Then, the next question is: Can digital recordings improve this situation?

The Adaptation is an inevitable process because there are three superimposed levels and also because it does not make sense to modify the procedure. Likewise, the transposition processes of the European legislation are not going to change. However, the recordings can be very useful in two ways:

- If the Recordings publish the situation of the spatial planning of each level and the state of the coordination among them in an up to date, complete and superimposable way. Then it is possible a) to obtain a more accurate idea of the situation, b) to keep an eye on the integration process to make sure it occurs and c) to establish policies in order to accelerate the process whenever there might be inefficiencies.

- If it is possible to carry out the updating of the current spatial planning with digital plans built up in the form of transactions (Systematization), will it be possible that those “change orders”, only when they involve formal modifications, may reach to be formulated and executed massively without altering the legal guarantees of the procedure?

The Feedback is also indispensable. Nowadays, the superior levels make soil policies begging for data or buying the data collected by expensive data collection processes. Digital recordings can be useful in two ways:

- The alterations of the current spatial planning which are controlled by the recording are susceptible of “being pushed upwards” automatically as soon as they are produced. Consequently, the superior level can select and extract the necessary data to update its system. They can have a real “control panel” nourished by the spatial planning’s dynamics of change. In the program of Urbanismo en Red there are web services which allow the SIU of the Ministry of Public Works to update itself automatically whenever the spatial planning of a municipality is updated.

- The unification of planning production tools to create transactional digital plans may also help “standardizing” (there is a lot to talk about this topic too) planning. Therefore, the basic concepts and parameters have to be conformed to a standard dictionary reached by consensus. These are the ones which have to “be pushed upwards” to the superior levels. This way, obtaining reliable and standardized indicators may no longer be a dream.

Eventually, the national and regional levels are not happy with obtaining data about the spatial planning, because they pretend to know also the success or failure of that spatial planning. This presupposes accessing to the urban planning management and execution local data. Whether accessing to the planning data without local and functional recordings is an impossible task, accessing to the urban planning management procedures and to the urbanization and building procedures so to be aware of the soil consumption and therefore the undeveloped land is science fiction.

However, this current impossibility must not stop us from thinking that this may be possible in the future. The digital recordings of planning can extend their range in order to comprise also the management and execution instruments. When this happens, it will be possible to know exactly the range of the urban planning process and to adopt real policies regarding needs or real problems.

This possibility justifies any effort made in order to provide the three levels with the necessary tools to keep recordings of urban planning and to turn the territorial instruments into digital transactions. This effort should help the municipalities to implant new management systems instead of just requesting them data, because data will arrive with these systems.